The Unz Review

http://www.unz.com/article/the-new-great-game-the-west-uyghers-and-china/

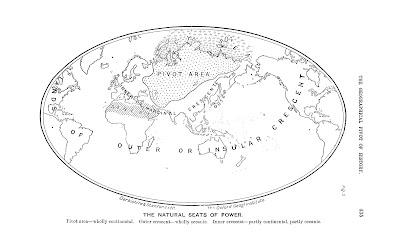

The control of Central Asia has been a core part of international

relations since the “Great Game” between Tsarist Russia and the British

Empire. At the turn of the 20

th century, John Halford

Mackinder developed the “Heartland Theory,” which revolves around the

concept of a pivot area/Heartland, that covers Eastern Europe, Central

Asia, Western China and most of Eastern Russia. The

theory determines that whichever regional power controls Eurasia will determine that country’s supremacy over world politics.

Mackinder’s theory had widespread traction. It was influential to

Nazi military planners, and the “Heartland” concept has been apparent in

United States foreign policy since President Jimmy Carter’s term in the

White House, when the US backed the mujahideen in Afghanistan against

the Soviet Union. Mackinder’s theory was pushed by then National

Security Advisor Zbigniew Brezinski, a voice still listened to in

Washington D.C. circles, and took on renewed relevance following the end

of the Cold War.

As a

leaked

1992 Pentagon document states: “Our first objective is to prevent the

reemergence of a rival that poses a threat on the territory of the

former Soviet Union. This is a dominant consideration… and requires that

we endeavor to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose

resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate

global power…Our strategy must now refocus on precluding the emergence

of any potential future global competitor.”

A decade after this policy objective, US forces were in Afghanistan,

and in 2010, the Obama administration launched its “pivot to Asia”

foreign policy initiative, its very name drawn from Mackinder’s

Heartland theory.

A clear aim is that the US and its allies – embodied in NATO – are

trying to contain China’s ascendancy to retain political and financial

power. There is the realization that power is shifting from the West to

the East. The US strategy has been proactive, trying to shore up its

allies in China’s immediate geographical vicinity, and been aggressive

in its military build up, particularly in Asia Pacific. But in Central

Asia, the US is on the back-step, unable to undermine Russia and China’s

strong positioning, evident in the Shanghai Cooperation Council (SCC).

Outside of the SCC, in the immediate area, the US is reducing troops in

Afghanistan – albeit to retain a presence until 2024 – and is not as

strategic a partner with Pakistan as in the past. The US is struggling

to have “

full spectrum dominance”

in Central Asia, and economically has been losing out to China, in

goods and services, to accessing hydrocarbons. Furthermore, China is

cementing its position in the area through its

Silk Road Economic Belt,

which is to run from China to Eastern Europe, and ramping up ties and

investment with neighboring Pakistan, evidenced in President Xi’s visit

to Islamabad with pledges of some US$46 billion. Additionally, China is

challenging the financial status quo regionally and further afield

through the launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AAIB).

Back to the Future

American policymakers were aware that exerting US influence in

Central Asia was going to be an uphill struggle, if not mission

impossible. Washington would not be able to have a military presence

with the same capabilities as in the Asia-Pacific, in Taiwan, South

Korea and Japan. Moscow would not stand for it, and neither would

Beijing. Afghanistan and Pakistan – known as AfPak – therefore become

focuses during and after the Cold War.

The NATO presence in Afghanistan has been devastating for the

country, and the US’ acquiescence in its relationship with Pakistan and

its infamous intelligence service the

ISI – which has

co-opted and used

Islamic terrorist organizations for its own ends to fight India in

Kashmir, and retain influence in Afghanistan – has created fertile

ground for extremists in the region.

As leaked documents have shown, this has been both intentional and

unintentional, with the US on one hand waging its “Global War on

Terrorism” and on the other creating the conditions for the rise of

Islamic terrorism – for instance ISIS spawned from the battlefields of

Iraq – and directly working with and through its allies with Islamic

terrorist groups.

In the wake of the Cold War, Britain and the US – along with Arab

Gulf allies – utilized Islamist groups, including fighters affiliated

with Al-Qaeda, for its own foreign policy objectives in Bosnia, Kosovo

and

Chechnya, documented in Mark Curtis’ book, which draws on declassified documents,

Secret Affairs: Britain’s Collusion with Radical Islam.

As cited in written evidence by Nafeez Ahmed to a

UK Parliamentary inquiry

in 2010: “According to Graham Fuller, former Deputy Director of the

CIA’s National Council on Intelligence, the selective sponsorship of

al-Qaeda terrorist groups after the Cold War continued in the Balkans

and Central Asia to intensify the rollback of Russian and Chinese power

(2000): ‘The policy of guiding the evolution of Islam and of helping

them against our adversaries worked marvelously well in Afghanistan

against the Red Army. The same doctrines can still be used to

destabilize what remains of Russian power, and especially to counter the

Chinese influence in Central Asia.’”

Covert operations programs have also been carried out by British and

American intelligence that supports certain Islamist opposition groups

in the Middle East to curtail Iranian and Syrian influence in the

region. This came to a head during the uprisings in the Arab world from

2011 onwards, with Western intelligence agencies working with funders

Saudi Arabia and Qatar to develop the militant opposition against the

regime of Bashar Assad in Syria, as has been documented

here,

here and

here. Turkey, a NATO member, has also been instrumental in supplying Islamic rebels in Syria, including ISIS (the Islamic State).

The move on Xinjiang

At the other end of the “Heartland”, Eastern Europe, the US and Europe have been involved in

regime change in Ukraine,

utilizing non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to undermine the Kiev

government away from the Russian orbit, and through backing pro-Western

politicians, despite in cases their openly

neo-Nazi and fascist sympathies.

A propaganda war has been waged in the West that has ignored the West’s

subversive policies in Ukraine to primarily demonize Russia, framing

the conflict as one of “freedom” and “democracy” and leading to renewed

discourse of a “New Cold War”. Such a policy has had mixed success,

still being played out, but is a clear geo-political attempt to

undermine Moscow in the public eye as well as economically through

sanctions. What is notable in the Ukraine arena is that the US has not

been directly involved militarily, relying on proxies and covert

operations, to not risk an all-out war with Russia.

Given the West’s track record with co-opting and using Islamist

groups for its own ends, as well as undermining democratically elected

governments that do not see eye-to-eye with the US since World War II

through coups and assassinations, it is far from conspiratorial to

suggest that such tactics will be employed in the future against Chinese

interests.

As such, Xinjiang is China’s Achilles heel, bordering on Kyrgyzstan,

Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as having

abundant hydrocarbons and being a key transit hub for the Silk Road

Economic Belt. As mentioned, the US is attempting to contain China in

the Asia-Pacific, and while it is strengthening its relationship with

India, does not have the same capabilities in Central Asia, which will

force the US to act clandestinely through NGOs, pro-democracy

organizations, and Islamist groups. For instance, the National Endowment

for Democracy (NED), which is funded by the US government and has been

linked to subversive measures in numerous countries, including most

recently in Hong Kong, is a

sponsor of the World Uygher Conference and the Uygher American Association.

This is given further credence by the Uyghers not having the same

‘appeal’ as the Tibetans when it comes to “information politics” and

winning “hearts and minds” in the West. The Uygher diaspora has

attempted to portray their political grievances as

self-determination

causes, ‘minority rights’ and ‘human rights’ to capitalize on media

coverage in the West. It is a classic method to highlight a cause in the

eyes of the Western public, concerned about human rights, women’s

rights and so on, the “softer” foreign policy issues. This was evidenced

in the media’s use of

humanitarian intervention

to justify the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, such as by

focusing on women’s rights and bringing “freedom,” thereby simplifying

the complex reasons for US military engagement.

But while the Uygher cause will not gain the same traction in the

West as Tibet arguably has – for one it is an under-covered area in the

media, and secondly the Uyghers’ Islamic identity can be considered a

“turn off” for liberal mainstream media – it is becoming a more

important issue in Islamic extremist circles.

A Jihadi Front Against China?

Beijing is aware of the international dimension of Islamic terrorism,

pressurizing Central Asian states to ban Jihadist groups such as the

Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) in Pakistan, the Islamic Movement of

Uzbekistan (IMU), the Islamic Jihad Union, and the East Turkestan

Islamic Movement (ETIM).

The TIP is linked to the IMU, which is pushing for the jihad to go

beyond Pakistan and Afghanistan into China. Its mufti, Abu Zar al-Burmi,

has become a prominent Jihadi leader in Pakistan with an anti-China

message that is reportedly gaining in popularity. In 2013, in a speech

called

“A Lost Nation”, al-Burmi said the “mujahideen should know that the coming enemy of the

Ummah

(the Islamic community) is China, which is developing its weapons day

after day to fight the Muslims.” In the speech, al-Burmi stated Muslims

should kidnap and kill Chinese citizens and target Chinese companies,

while blasting the Pakistani-Chinese relationship.

In May, 2014, Reuters briefly

interviewed

TIP’s leader Abdullah Mansour, who echoed al-Burmi’s statements. “The

fight against China is our Islamic responsibility and we have to fulfill

it. China is not only our enemy, but it is the enemy of all Muslims …

We have plans for many attacks in China,” he told Reuters. “We have a

message to China that East Turkestan people and other Muslims have woken

up. They cannot suppress us and Islam any more. Muslims will take

revenge.”

It is highly probable, lacking other options and not able to go head

to head with Beijing, that the US will capitalize on such sentiments,

urging directly and indirectly attacks against Chinese interests in

Central Asia and China itself, as well as further afield, utilizing

networks in Pakistan and the Middle East.

A scenario, going by past example, would be to force Beijing’s hand

into harsh crackdowns against the Uyghers in Xinjiang, thereby providing

ample propaganda opportunities for Jihadi groups to label China as an

enemy of Islam, for Western media to highlight the Uygher’s aspirations

for self-determination, and draw China into a costly war that will

destabilize the Silk Road Economic Belt initiative.

The US appears to have already utilized such a strategy. “Between

1996 and 2002, we, the United States, planned, financed and helped

execute every single uprising and terrorism related scheme in Xinjiang

(aka East Turkistan and Uyghurstan)”, said

Sibel Deniz Edmonds,

a former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) translator and founder

of the National Security Whistleblowers Coalition (NSWBC), under oath in

the US.

Militant Uyghers in the AfPak arena pose the closest geopolitical

threat in this regard. Elements of Pakistan’s ISI in conjunction with

financiers in the Arabian Gulf, as well as through establish networks

with Western intelligence agencies, would pose the greatest concern.

Indeed, as in the past when Islamabad played off British and American

interests to maximum advantage, so could it play off its main financial

backers, China, Saudi Arabia and the US.

Turkey is also a player to be watched in this regard, trying on the

one hand to not sour growing ties with China, and on the other keep its

affinities and further strengthen relations with

Turkic

groups. Istanbul has played a major role in the rebel movement against

Assad, while the country is home to a large Uygher diaspora.

Furthermore, with Turkey a transit hub for rebel groups to enter Syria

and Iraq, it has played a role in enabling

Chinese Muslims and Uyghers to join ISIS and become radicalized.

Another “Great Game” is unfolding, and the Heartland of Eurasia will

be a key arena in the battle for the US to retain a unipolar world, or

make room for a multilateral one, which Washington will fight on all

fronts to ensure does not happen.

As Brzezinski wrote in

The Grand Chessboard, echoing

Mackinder: “The US, a non-Eurasian power, now enjoys international

primacy, with its power directly deployed on three peripheries of the

Eurasian continent [...]. But it is on the globe’s most important

playing field – Eurasia – that a potential rival to America might at

some point arise”.